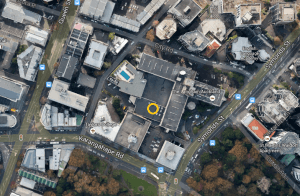

The Langham is one of Auckland’s new breed of 5-star hotels. Its placement high on the Karangahape Ridge affords views across the central city and out to the Waitemata Harbour, as well as inland to Grafton, Mt Eden and Parnell. For 22 years this was the Sheraton, until new owners, a new name, and a $12m remodel came along in 2005. But before the Langham, before the Sheraton, there was a windmill. Not something you would associate with this part of the world, but Partington’s Windmill was, for exactly 100 years, a significant central Auckland landmark. Here’s the story.

When English-born carpenter Charles Partington arrived in Auckland in 1842, the city was a newborn. Only recently named, it was still, for a brief moment in our history, the nation’s capital. In an age when even domestic supplies were moved by ship, a city’s ports were the heart of its business districts, and urban development fanned out around them. Consequently Auckland’s commercial district ran barely half a kilometre up from the waterfront to about where Wellesley St is now, with farmland as far as the eye could see beyond that. Other communities had already begun to germinate around the ports of Onehunga, Panmure and Howick.

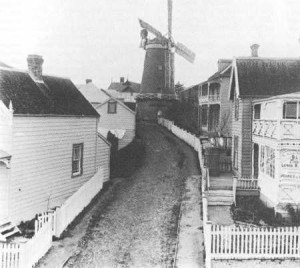

Entering into a business partnership with one John Bycroft, Charles Partington took over the Epsom Mill for a short time, Epsom being mostly wheatfields in those days. By 1850 however the partnership was dissolved and Charles was looking for new opportunities closer to the blossoming downtown district. Finding a suitably prominent location near the intersection of Symonds St and Karangahape Rd, he purchased three adjoining sections of land and commissioned the building of a windmill six stories high. The 27 inch thick walls were formed with nearly 100,000 wedge-shaped bricks cast using clay dug from the site itself, and the four wooden sails had a span of over 60 feet (18.3m).

Initially, Charles Partington used his windmill to grind other people’s grain into flour on a customer-by-customer basis, using the pressure of four one-ton concrete stones propelled by the westerlies blowing in from the Waitakeres. However, in 1851 he built a small factory on the property and began buying grain to produce his own food, and this ability to grind the flour and manufacture baked goods in-house soon established Partington’s new business, the Victoria Flour Mills and Steam Biscuit Depot, as a major firm. The growth continued when he was awarded a lucrative contract to produce biscuits for British troops during the Land Wars of the 1860’s.

That decade also saw Charles Partington diversify into other business interests. The biscuit factory was still the backbone of his enterprise, but he leased the windmill out to other operators, built a watermill in Riverhead, and felt the fever of the Thames gold rush. The steam biscuit factory received a major refit in 1866, but a major fire later that year may have dampened Charles’ enthusiasm for the bakery trade. With the buildings uninsured and his businesses in decline, the newly imported machinery was shifted to the Riverhead watermill, and by 1872 advertisements for fresh biscuits were replaced with ones offering his Symonds St properties and milling equipment up for sale.

By this time the windmill had been a familiar feature of Auckland’s skyline for only 20 years, but was already established as both a popular vantage point for photographers, and as a navigation reference for passing ships. Unfortunately it had already been superseded by steam powered milling equipment, and if the land sections were sold it was expected to be demolished. As luck would have it, though, only the state-of-the-art biscuit making plant in Riverhead attracted a new owner, so the windmill stayed.

Charles Partington died in 1877, leaving the remnants of his empire to his wife. A brief flurry of legal tussles between his eight sons ultimately left business matters in the hands of Henry, Charles F., and Joseph Partington. Milling resumed at the Symonds St premises, but differences between the brothers caused a split, with Henry and Charles F. advertising the land and buildings for sale once more, and Joseph, in the same newspapers, publishing notices stressing that he had no intention of relinquishing the property. By 1890 Joseph had successfully defended his ownership of the factories and windmill, but was bankrupt. He had no choice but to sell a portion of the Symonds St block, including the mill, and lease it back from the new owner.

Today’s reader may find it interesting to note that the factory went on producing its wholemeal biscuits and breads, which Joseph had begun promoting as “health foods”. Particularly proud of his own creation, pearled wheat, his products contained “no baking powder, yeast, chemicals, animal fat, or inferior butter”, his adverts promised. This must have been a fairly novel marketing angle a hundred years ago.

Further legal wrangles seemed to plague Joseph Partington and his windmill over the remainder of the 19th century. His landlord, James Wilkinson, sold a portion of the land adjacent to the windmill. When Partington learned that the new owner intended to build a two-storey horse stable – restricting wind flow as well as access to the sails for repairs – and he petitioned the council to prevent its construction. When this was unsuccessful, he undertook a childish personal attack on Wilkinson, commissioning a free pamphlet titled “The Story of the Windmill”. However, its real motivation was revealed in the subtitle:

“Gross Negligence or Rank Favouritism on the Part of the City Council

How To Obtain a Building Permit By False Pretences”

Within the booklet Wilkinson was referred to as “an avaricious and flint hearted landlord”, which earned Joseph a libel lawsuit, which he lost. Unable to pay the fines he was, for the third time, rendered bankrupt in 1898, but still living on the property, working in his biscuit factory, and in fact residing in the same building as James Wilkinson and his extended family in a split house located astride the boundary line. It can’t have been an easy time for either man.

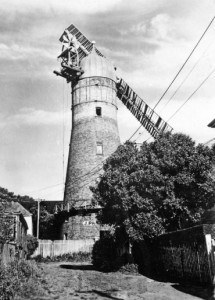

Wilkinson removed the four giant sails from the windmill in about 1903-04 so that new ones could be fitted, but this was clearly not a priority and new sails failed to materialise. Instead he began hawking the structure to the city council, extolling its virtues as a tourist attraction and public viewing platform. These proposals were rejected by the authorities, at least at the price offered, and the old mill languished, unused and looking more-or-less like a lighthouse, for another few years. When Wilkinson finally found a buyer, it was none other than his arch-enemy Joseph Partington, who finally purchased the windmill back in 1910, vowing to return it to a functioning state. On another point he was also very clear: he would never part with an inch of his land again, for any sum.

But Auckland’s development had overtaken the windmill. Not just technological progress, but also the vertical progress of the surrounding suburbs. Where sixty years before Partington’s mill had been exposed to the four winds, much of this was now deflected by the predominately two and three storey buildings clustered around it. It would be several years before a solution could be found, and in the meantime Joseph continued to operate solely out of the factory.

In 1914 he finally found the motivation, and most likely the funds, to give the windmill a makeover. Voyaging to England he sourced a condemned windmill and bought the sails, machinery, and its ornamental metal cap, shipping them all back to Auckland along with a quantity of the brickwork. Using the bricks he added fifteen feet (4.6m) to the height of his mill, attached the sails (which featured self-regulating shutters), and augmented them with a gasoline engine so that things would be business as usual on even the stillest days. Partington’s windmill was reborn for the 20th century!

All was well until a severe storm tore off one of the sails in May of 1925, and to maintain balance the opposing sail had to be removed. Joseph pledged that the damage would be repaired and the mill would return to its heyday once more, but this never came to pass and the mill would remain two-bladed for the rest of its years. The final blow was a devastating fire in 1931, beginning in one of the adjacent buildings. Spreading to the windmill it was further fuelled by the many bags of wheat and grain stored on the lower levels, and from there it funnelled upwards, vapourising the ten wooden floors and staircases, and charring the two remaining sails.

The massive, prehistoric machinery survived, though. Repairs were made, at least to the extent that the iron helmet was remade, and internal floors rebuilt, but by now Joseph was in his 70’s and despite again vowing publicly to restore the windmill to its four-bladed glory it may have never resumed operation. At some point the old man had a dispute with staff in his factory and closed that down, as well. During the 30’s the mill, and most likely the adjacent buildings, served as an occasional youth hostel, a night club, and slowly fell back into disuse and disrepair. Joseph had his lawyer draw up a last will and testament bequeathing the windmill to the city upon his death, and wishing that the land surrounding it become known as Partington’s Park. It was a grand gesture but the council seemed concerned about the practicalities of maintaining an antique windmill. In any event, Joseph’s will was never upheld, so they were spared the dilemma of what to do with the unwanted inheritance.

Joseph Partington finally passed away in 1941. The Auckland Star of September 28th wrote, rather melodramatically:

“Slumped back in a chair in the kitchen of his home under the shadow of Auckland’s oldest and most romantic landmark, the dead body of Mr. Joseph Partington, proprietor of the windmill near Grafton Bridge, was found by a tradesman at 11.30 a.m. to-day. There were the remnants of a meal upon a bare table beside which Mr. Partington had been sitting, his bed upstairs had not been slept in, and there was other evidence suggesting that death had come to the old miller suddenly. He was 83 years of age – only 14 years younger than the historic old mill itself, which he had tended since boyhood”

A search of the premises turned up numerous packages of cash – envelopes, boxes, tins, and cans – all labelled with the enclosed amounts and totalling several thousand pounds.

With Joseph no longer around to obstinately defend his property in the face of financial logic and commercial progress, his windmill, inevitably, was on borrowed time. In absence of proof of will, the land and assets, rather than becoming Partington’s Park, was divvied amongst an array of cousins, nieces, and nephews, who promptly sold it to automobile dealers Seabrook Fowlds Ltd. They wasted no time in bowling the derelict factories and outbuildings but, initially at least, pledged to let the windmill stand. It certainly would have made their dealership easy to find.

Evidently their sense of history evaporated within a year or two, but in fairness they consulted the council about the possibility of preserving the structure…just somewhere else. The council formed the “Old Windmill Preservation Society” in 1945, whose purpose was to raise monies to pay for the relocation. Ultimately the public did not feel strongly about the cause to meet the target, and there was some trouble agreeing on a suitable location for a ten storey icon. The concept was shelved.

Now committed to demolishing the windmill, Seabrook Fowlds presented the council with a new plan: if the city paid for the demolition, they could keep whatever materials they wished, in the event that a suitable location and budget became available in the future to rebuild the mill. The council declined, suggesting that there was very little worth saving, and that Seabrook Fowlds might like to “donate” the machinery for use or display at Western Springs. The Western Springs pumphouse would later form the basis of Auckland’s Museum of Transport and Technology, so this would have been and ideal resting place for the dinosaur machinery and four one-ton millstones. This is not what Seabrook Fowlds had in mind, and they resigned themselves to removing the windmill at their own cost. Work began in April 1950. The hand-cast bricks almost certainly went into a landfill, the machinery and metal cap melted down and recycled as far more mundane products, and the huge millstones broken up and hauled away.

The whole sad business may have been inevitable at the time, but in retrospect the Auckland City Council appear to have turned their backs on perhaps the single most historic building on their patch. If there is a silver lining here, the windmill’s destruction seems to have been a wake up call for both council and citizens, and much work was done following its loss to protect dozens of other heritage sites from the same fate.

Meanwhile, at the lavish Langham Hotel, there is little reference to the legacy of the Victoria Flour Mills and Steam Biscuit Depot upon whose site it stands. Except for the award-winning dining, which you can sample at Partington’s Restaurant.

For more information on Partington’s Windmill, Timespanner have written a very detailed and well researched article on it.

For more information on the Langham Hotel, see their website.